by Leon Kolankiewicz

Continental Divide along US 26 in Wyoming in late May 2024

On the final day of my recent travels through the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, I made an excursion into its southeastern reaches in the Wind River Indian Reservation. To reach these secluded hinterlands from Jackson Hole, I followed US 26 from Moran Junction through the Bridger-Teton and Shoshone national forests and up to and over Togwotee Pass, the frozen Continental Divide at nearly 10,000 ft elevation. Snow still blanketed these rugged heights.

Togwotee Pass is named for a subordinate of Chief Washakie of the Shoshone Indians. Togwotee guided the Jones Expedition (a survey team) over this pass in 1873 (the year after Yellowstone National Park was created), but for a long time before that it was already an important trade route for indigenous tribes in the region.

Raindrops and snowflakes falling on the eastern flank of the divide here flow into the Wind River, and thence into the Bighorn, Yellowstone, Missouri, and Mississippi rivers, ultimately pouring into the Gulf of Mexico if they aren’t diverted to irrigate row crops or to slake the thirst of townsfolk first.

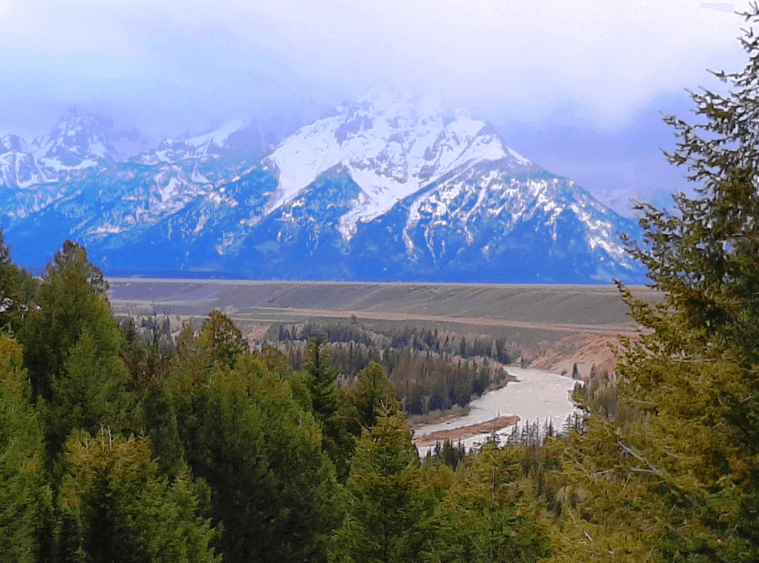

On the west side of the divide, waters wend their way to the Snake River, a tributary of the mighty Columbia. This great river eventually empties into the Pacific Ocean northwest of Portland, Oregon, after gathering further hydrologic tributes from its vassals in the Columbia Basin – Pacific Northwest watercourses such as the Umatilla, John Day, Deschutes, Willamette, Lewis, and Cowlitz.

Snake River and the Teton Range in Grand Teton National Park, May 2024

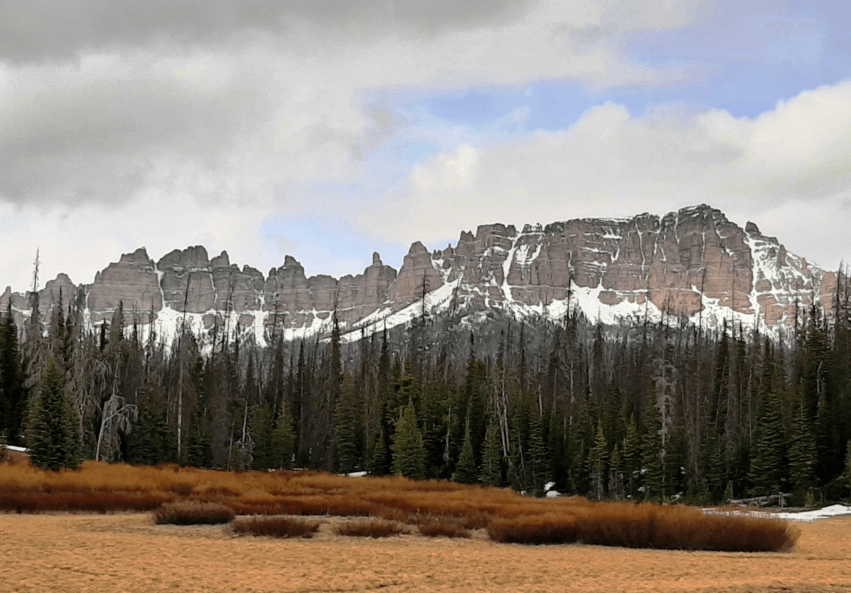

North Breccia Cliffs (11,007 ft.), Bridger-Teton National Forest, from US 26; late May 2024

The scenery of the Bridger-Teton and Shoshone national forests along US 26 is breathtaking in its sheer variety and geomorphological complexity. The serrated, dramatic North Breccia Cliffs for example – visible right from the highway – are composed of volcanic breccias (coarse-grained rocks made of angular volcanic fragments), conglomerates, and tuff (a rock made from volcanic ash ejected in eruptions).

According to the U.S. Forest Service,

These cliffs are part of the southernmost portion of the Absaroka Range, and it is thought that Absaroka Eocene age [56 to 34 million years ago] volcanism was rapid and violent. This often-overlooked range is quite spectacular. Originally formed from eruptions that piled volcanic debris, the forces of erosion and glaciation have since sculpted spectacular topography.

Fort Washakie Pow Wow on the Wind River Indian Reservation

Photo: Wyoming Office of Tourism

Established in the late 19th century, the 2.2-million acre Wind River Indian Reservation is about the size of Yellowstone National Park itself, and is the 7th-largest Native American reservation in the United States. It is home to the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes. The reservation is situated in a region that was historically used by many tribes for hunting and raiding, including the Arapaho, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Crow, Lakota (Sioux), and Shoshone. The iconic Shoshone guide of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806), Sacagawea, is said to be buried at Fort Washakie on the Wind River Reservation and has a marker there, though the accuracy of this account is disputed.

Wind River Wild Horse Sanctuary

Photo: Wind River Country

The Wind River Basin used to support vast herds of bison. Today there are greater numbers of horses and cattle, but the Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative is “on a mission to restore Buffalo through land rematriation, community revitalization, and youth education,” guided by a vision of “thousands of Buffalo on tens of thousands of acres, protected under Tribal law as wildlife.”

Unfortunately, all I could do is scratch the surface of this rich tapestry of natural and human history. I decided to aim for the village of Crowheart, whose name I found intriguing. But as I was soon to learn, the story, or legend, behind that name was even stranger than I thought.

Wind River Range on the Indian Reservation of that name in western Wyoming

Photo: Jennifer Strickland, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

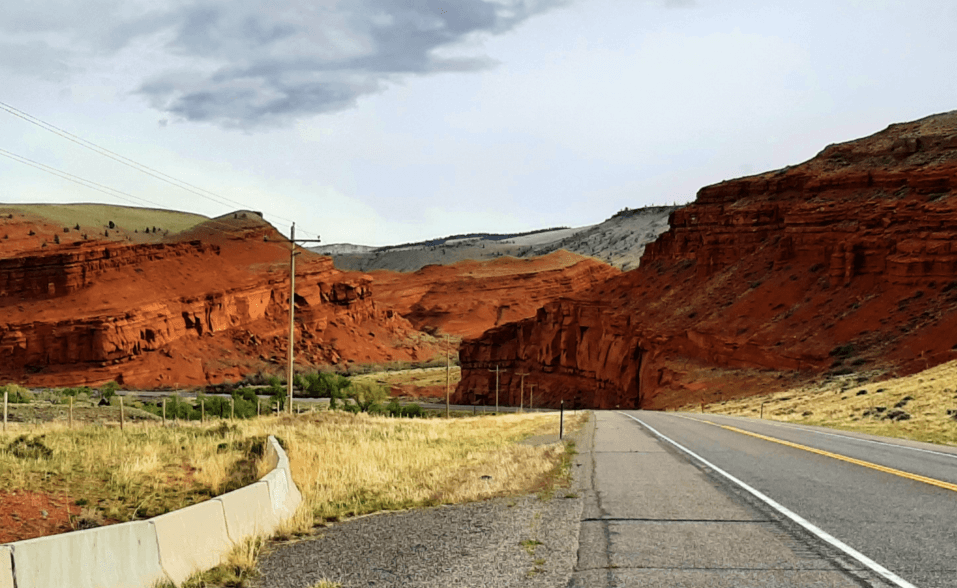

Red rocks on the Wind River Indian Reservation from US 26; May 2024

As I approached the reservation, descending from the lofty crest of the Continental Divide behind me to the west, the rain-shadowed landscape grew much drier at these lower elevations, dominated by rangeland, sagebrush, and tumbleweed – evocative scenery that all Americans recognize from a slew of Hollywood Western films. I was reminded of the classic 1912 Western novel Riders of the Purple Sage by Zane Grey, and its gunslinger Jim Lassiter, though this fictional story was actually set in neighboring Utah.

Wind River Range from US 26; May 2024

Crowheart Butte

Photo: Greg Westfall/Flickr Creative Commons

As I drew closer to tiny Crowheart, its namesake came into view. That would be the striking 6,772 ft. Crowheart Butte. Here is how the name Crowheart came to be according to a descendant of one of the principal figures in the violent and perhaps at least somewhat apocryphal or legendary clash that it stems from: the Battle of Crowheart Butte.

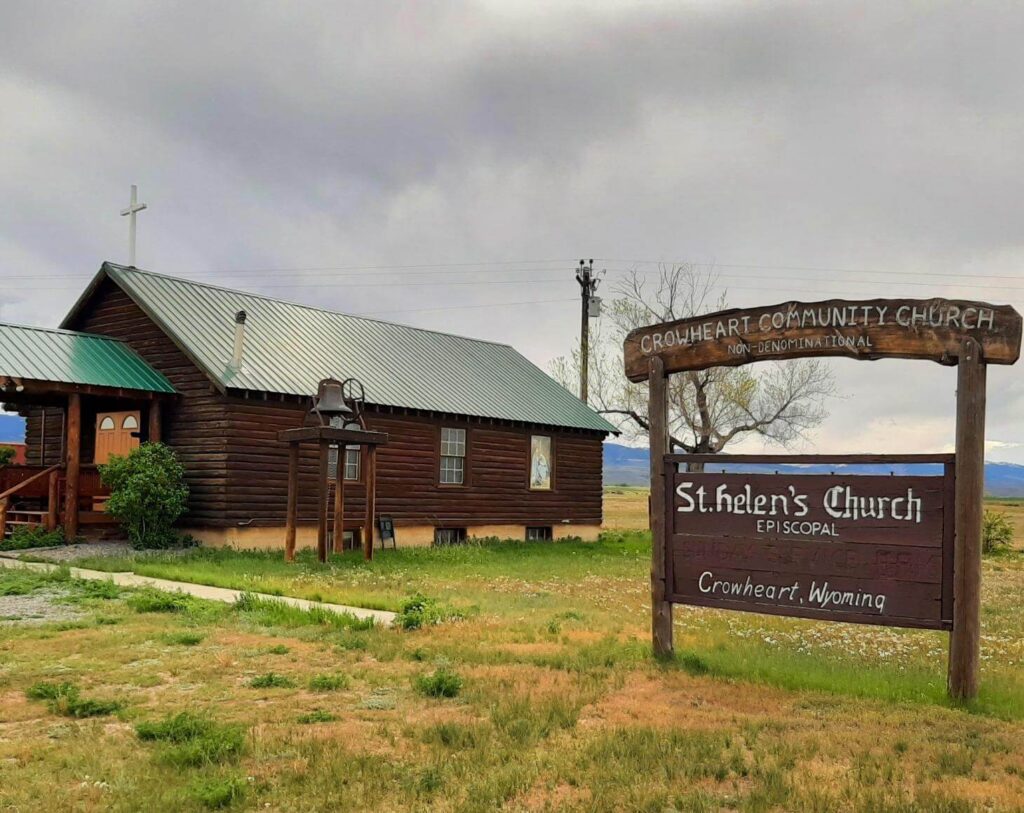

St. Helen’s Church in Crowheart, Wyoming, on the Wind River Reservation

The Shoshone had long lived in the Wind River Valley but in 1866 clashed over hunting rights in the Wind River Range with Crow Indians who had been displaced westward by encroaching Euro-American pioneers. According to one of his descendants, Chief Washakie (c. 1810-1900) of the Shoshone attempted to negotiate with the Crow but they killed the envoy he sent. This triggered a brutal battle between the Crow and the Shoshone in the shadow of the dramatic butte.

After five exhausting and deadly days of fighting, Chief Washakie approached the Crow’s chief Big Robber and proposed single combat to the death between the two chiefs to settle the matter and prevent further bloodshed of their warriors.

The people whose champion lost would respect the outcome and leave. Big Robber agreed. Washakie…left the parlay with a promise to Big Robber: “When I win, I’m going to cut out your heart and eat it.”

Legend has it that Washakie vanquished and killed Big Robber, but impressed with his courage, instead of eating his heart, he impaled it on a lance and rode back with it into the Shoshone camp.

That is where the name “Crowheart” comes from. I recount this grizzly story here merely to convey a sense of the extraordinary human history, culture, and drama that are also part and parcel of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.