In nearly four decades of writing about wildlife conservation issues and their intersection with human-built environments, I’ve often confronted this challenge: how to make the consequences of population growth more understandable to readers who believe “growth just happens” to both places and people. Routinely, they harbor the mistaken impression there’s little that can be done to mitigate it. Few, in fact, do much reflecting on their own ecological footprint and how it ripples collectively on a landscape level.

A few short years ago, I was working on an investigative story about the impacts of inward migration— of Americans moving from one place to another for largely lifestyle considerations. Their primary motives were wanting to escape crowded urban areas, to take advantage of remote working options, and, frequently, out of a desire to “live closer to nature.”

The focus of my narrative was not on just any region. The area of interest was the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE), a vast complex of public and private lands readily visible from my home in Bozeman, Montana.

Greater Yellowstone, if you’re unfamiliar with it, has Yellowstone, the first national park in the world, at its geographic heart. The ecosystem that encompasses the park is today considered the most iconic wildlife-rich bioregion in the Lower 48 states, renowned especially for its concentration and diversity of large free-ranging native mammal species rescued from near-annihilation at the end of the 19th century.

There are compelling scientific reasons why Greater Yellowstone is often compared with another famous reference point for large mammals—the Serengeti Plain in East Africa.

Somewhat surprisingly, I’ve discovered, many Americans are more familiar with species on the Serengeti, owed to the popular Disney animated film, The Lion King, than they are with Greater Yellowstone.

Many are shocked to discover that equal levels of drama can be found in the backyard of the West. One can watch howling wolves hunting bugling elk; see wild herds of bison and pretend it’s a scene from 200 years in the past; savor the presence of famous Jackson Hole Grizzly 399 and generations of her cubs; and stroll through the ethereal geothermal basins of Yellowstone and believe you’re on another planet.

Here, where I live, there are Yellowstone and neighboring Grand Teton National Park. Encircling them are five different national forests, three national wildlife refuges, a large sweep of federal land administered by the Bureau of Land Management and the Wind River Indian Reservation, home to the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone nations. Notably, Wind River is almost identical in size to Yellowstone and its 2.2 million acres, which at roughly 3,500 square miles is larger than Rhode Island and Delaware combined.

In all, of Greater Yellowstone’s roughly 23 million acres, three quarters of it is public land and the last quarter is comprised of private property, including working farms and ranches.

While the private land component is a fraction of the amount of public acreage that belongs to all American citizens, it serves a critical ecological function.

In the larger picture of the American West, Greater Yellowstone resides at the intersection of three states—Wyoming, Montana and Idaho. Rising from it are the headwaters of three major U.S. river systems—the Yellowstone-Missouri-Mississippi; the Snake-Columbia; and the Green-Colorado that, in turn, empty, respectively, into the Atlantic, the Pacific, and the waters of Baja, Mexico.

Historically, Greater Yellowstone has benefitted from four factors: its geographic remoteness, sheer mass of public lands, low human population and the fact that the preponderance of private land was either agricultural or undeveloped. Three of those variables—remoteness, low human population and development that is clustered primarily around cities and towns—no longer exist.

As I was doing my research about the impacts of population growth and the corresponding expanding footprint of development in Greater Yellowstone, I met with a highly respected conservation biologist named Brent Brock who had devised a computer modeling program that he called Wild Planner. During one of our many visits, he invited me over to his computer and said, “Hey, look at this.”

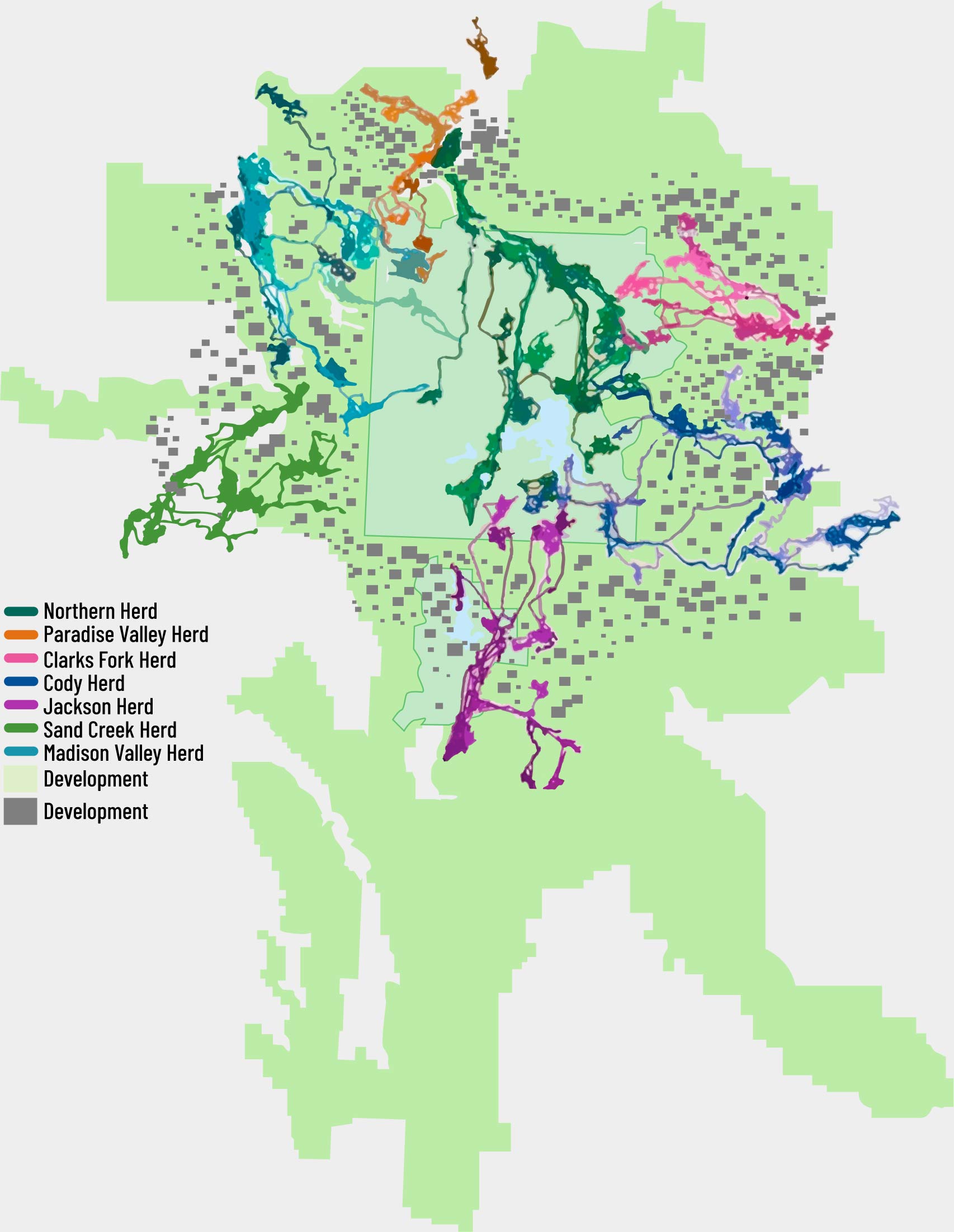

In rapid succession, Brock typed in data that came from a number of reputable sources ranging from the U.S. Census Bureau to state cadastral maps. Soon we were looking at the proliferation of recent residential subdivisions that had sprouted in exurban areas of three counties— Gallatin, Park and Madison— in the northern tier of Greater Yellowstone. The results were jaw dropping, and then Brock plotted in the likely locations of new development and how they would replace working farms and ranches. It revealed a pattern that, if left unchecked in coming decades, would leave some of Greater Yellowstone’s major wildlife migration corridors, important to the movement of elk, pronghorn, mule deer and other species blocked or severely constricted. The longest known migrations for elk, pronghorn and mule deer in the world exist in this ecosystem.

While standing next to Brock, who passed away tragically from cancer in October 2023, I will never forget something this forward-thinking conservation biologist said: “Sprawl kills.” It has an established record of being a destroyer of wild ecosystems and, unless things change, unbridled growth is going to ruin many of the things that still set Greater Yellowstone apart as an American national natural treasure. The most obvious manifestation, Brock said, will be fragmented landscapes that result in wildlife being no longer able to navigate between key seasonal habitats.

Two large-landscape thinkers, Dr. Matthew Kauffman, a federal USGS scientist spearheading the Wyoming Migration Initiative, and Dr. Arthur Middleton, based at the University of California-Berkeley, have likened Greater Yellowstone’s migration corridors to the circulatory system of a human body. Block the arteries or passageways leading to the heart or lungs and serious negative consequences are certain.

Where Greater Yellowstone is considered a beacon of modern wildlife conservation globally, touted as the emblem of a healthy intact ecosystem in America and known for its successful rewilding of several species, its legacy, Brock said, could be one of permanent de-wilding unless trendlines are altered.

Here, I will invoke the perspective of another big picture thinker, former Yellowstone science chief David Hallac who said there is the usual array of large obvious challenges facing Greater Yellowstone but more insidious is what he calls “death by 10,000 scratches” involving a constant onslaught of new structures, roads, and infrastructure, much of it taking scattershot form across rural lands.

Assessing the impacts of sprawl is important no matter what the geographical setting, but in here it takes on added significance. Greater Yellowstone is the only bioregion remaining in the Lower 48 states with all of its original species that were present in 1491, the year before Europeans arrived on the continent. A crucial question readers should ask is: why have the caliber of wildlife attributes present in Greater Yellowstone been lost mostly everywhere else? Once you’ve pondered that query, pay special attention now to this study you hold in your hands—a scientific examination/overview of how the rapidly-expanding human footprint on private land in Greater Yellowstone is shaping the prospects for species survival today and in the future.

To date, few studies have taken a deep dive look at the intensifying effects of sprawl on a wildland-wildlife ecosystem like Greater Yellowstone. Not only is such an examination long overdue, but it is especially poignant—and timely. Inward population growth and an ever-expanding human footprint were serious concerns before the arrival of Covid. But during the pandemic three things happened: the pace of exurban sprawl on private rural land accelerated as more newcomers moved into the region; subdivisions supplanted former farms and ranches like never before; and the intensity of outdoor recreation pressure on public lands increased markedly.

Photography by Holly Pippel

The result is wildlife being squeezed out of optimal habitat formerly available on private land, and recreation pressure displacing species on public land. On top of it, whether one believes that climate change is caused by humans or not, meteorological data show the region has become warmer and drier; a testament to that is not only that there are 30 additional days each year in which the temperature doesn’t fall below freezing, but larger forest fires are becoming more common. Dr. Cathy Whitlock, a Montana ecologist and fellow with the National Academy of Sciences, led a series of reports on climate change, including one for Greater Yellowstone that forecasts major ecological disruptions related to water availability and use, fires and drought.

Why is the risk of property loss growing every day? Because more people than ever before are building their dream homes inside the forested wildland-urban interface, which also happens to represent a critical zone of connectivity for species moving between public and private lands.

One may wonder: what’s the connection between healthy ecology and economy in Greater Yellowstone? Every year, the National Park Service releases findings of an annual assessment gauging economic impact. One recent analysis found that Yellowstone and Grand Teton parks alone generated $1.5 billion in economic activity for the surrounding communities and that commerce was responsible for creation of 15,000 jobs. Besides the allure of seeing Old Faithful Geyser erupt, grizzly bear and wolf watching opportunities were the top attractions.

In 1995, researcher William Newmark published a peer-reviewed paper titled Extinction of Mammal Populations in Western North American National Parks. He noted that even in other large parks similar to Yellowstone, species over time still vanished. The reason was they were inadequate, by themselves, to sustain wide-ranging terrestrial species. In 2023, Newmark and colleagues published an updated analysis in the respected journal, Nature, and again observed that big parks aren’t big enough. In particular, he alluded to national parks becoming isolated and islandized inside a sea of sprawl:

“Protected areas are the cornerstone of biodiversity conservation worldwide. Yet the capacity of most protected areas to conserve biodiversity over the long-term is under threat from many factors including habitat loss and fragmentation, climate change, and over-exploitation of wildlife populations. Of these threats, habitat loss and fragmentation on lands adjacent to protected areas are the most immediate and overarching threats facing most national parks and related reserves in western North America. As a result, most parks and related reserves in western North America are becoming increasingly spatially and functionally isolated in a matrix of human-altered habitats. This is particularly problematic because few parks and related reserves worldwide are large enough to conserve intact plant and animal communities and many large-scale ecological processes, such as mammal migrations and disturbance regimes [such as wildfires, floods, droughts and disease outbreaks affecting species].”

Yellowstone and Grand Teton are not drive-thru zoos. They have no fences encircling their perimeters. As Newmark noted, these national parks are not big enough, by themselves, to maintain the survival of species found inside them. Wildlife needs room to roam. The vast majority of species in Greater Yellowstone rely upon private land habitat to stay alive and indeed private lands function as critical passageways between public lands.

When it comes to migration routes and particularly “pinch points” where the size of the corridor is narrow, a new subdivision of just 100 homes and organized as 20-acre ranchettes could, in some places, impair the ability of wildlife to migrate. This is an example of what Kauffman and Middleton say is analogous to a blood clot in a human body, blocking the circulatory system.

Allow me to offer some added context. A few decades ago, a group of researchers concluded that a new residence and outbuildings constructed on a section of land (640 acres or one square mile) would displace a grizzly bear mother and cubs. It’s important to note that a different scientific analysis showed that secure habitat which supports grizzlies is beneficial to more than 230 other species of mammals, birds, fish, and amphibians. During a recent chat, the head of the Gallatin Valley Land Trust told me that for every acre being protected through conservation easements, two acres are being lost to development—and that trend does not include the amount of acreage that already is covered by leapfrog sprawl. That ratio is comparable to many valleys in Greater Yellowstone.

Only a generation ago, the total human population for the entire ecosystem was around 460,000. In 2017, I met with population demographers and planners and wrote a story about growth trends in Greater Yellowstone. Remember, this was prior to Covid and the effects it brought. I turned first to Bozeman and Gallatin County which had a combined population of about 110,000.

Less than a decade ago, Bozeman and Gallatin County were growing at rates of around three to four percent annually. Based on a conservative trajectory of three percent, that meant that Bozeman/Gallatin would double in population in 24 years, meaning that it would have a population equal to today’s Salt Lake City proper. It also means that if that growth rate continues, it would double again in 48 years, becoming the size of Minneapolis proper (440,000) by around 2065.

In the southern half of Greater Yellowstone, a corridor of towns between Idaho Falls, Idaho, running through Jackson Hole and connecting other mountain valley communities, there is today a population roughly equivalent to the size of Salt Lake City proper (250,000). That total volume of humans is expected to double within a generation. In addition, there are many spillover effects happening from Bozeman and Jackson Hole into neighboring valleys.

Photography by Holly Pippel

Sure, you might have highly-adaptable white-tailed deer and coyotes roaming golf course fairways on land that was previously a ranch with a tiny imprint of buildings, but gone is secure habitat for more sensitive species such as free-ranging elk, mule deer, pronghorn, moose, grizzlies, wolves, bighorn sheep and wolverines. No matter how one feels about livestock, working ranches with cows are far better than a meadow covered in condos, for as long as the land base is intact, wildness has a better chance of persisting and it represents places where re-wilding can occur.

Recall again my earlier reference made by scientist David Hallac about Greater Yellowstone suffering a death by 10,000 scratches. While individually each of these scratches may be insignificant, it’s the cumulative effects that exact a mighty consequential toll.

Public land managers can take steps to address the impacts of traditional natural resource extraction or lessen the pressure of outdoor recreation on wildlife by limiting numbers of users, but on private land, infrastructures of concrete, steel, wood and asphalt cannot be undone. Every new subdivision comes replete with buildings, driveways, fences, non-native vegetation, roaming and barking dogs, domestic cats that kill songbirds, non-natural foods that can serve as wildlife attractants and result in animals getting removed, a cacophony of noises, and light pollution that drowns out the starry night skies. People who build their dream homes on the edge of national forests and then get worried about fire after the fact often end up logging the forest as a tactic of prevention yet they don’t realize it destroys habitat.

I have file drawers full of papers written by leading scientists that speak to the points above. As has been conclusively established, island populations of species disappear at higher rates than those which are sustained over large unfragmented areas. Destruction is subtle and by the time it becomes visible to humans it may be too late to reverse. Newmark and co-authors wrote: “Most species extinctions in habitat remnants, including protected areas, following habitat loss are not immediate, but occur after a time lag. The lag in species loss over time is because many species that occur in habitat remnants do not have viable populations. The delayed loss of species over time in habitat remnants is referred to as relaxation or faunal collapse.”

In 2009, Dr. Andrew J. Hansen, a professor of ecology at Montana State University wrote an analysis titled “Species and Habitats Most at Risk in Greater Yellowstone” for the journal Yellowstone Science. He shared his ongoing analysis of development patterns at dozens of different sites in the ecosystem.

“Developed land has increased faster than the rate of population growth. While the GYE experienced a 58 percent increase in population from 1970 to 1999, the area of rural lands supporting exurban development increased 350 percent,” Hansen wrote. He noted that riverside habitats, also known as riparian areas, rank among the most important for maintaining biodiversity. “Of the many miles of rivers flowing through private lands in the area, 89 percent of the streamsides are within one mile of homes, farms or cities. Among aspen and willow habitats, critical for wildlife, only 51 percent of those on private lands in the Greater Yellowstone area are more than one mile from those more intense human land uses.”

Hansen laid out a litany of negative cascading effects of sprawl and rural development on a wide range of species and showed that development was occurring disproportionately in exurban settings which still provide high quality wildlife habitat. Chastening is that when I spoke with Dr. Hansen again in 2024, those breathtaking trends that he identified in 2009 accelerated prior to Covid and then erupted during the pandemic. In 2022, Hansen was lead author on a paper, “Informing conservation decisions to target private lands of highest ecological value and risk of loss,” that appeared in the journal Ecological Applications. Scientists said protection of the last best remaining private land habitats needs to be prioritized.

What this important study led by Leon Kolankiewicz with Roy Beck and Eric Ruark does is put the permanent ecological costs of sprawl into perspective, clear-mindedly providing an overview that citizens, elected officials, public land managers, private property owners, business people and conservationists can understand. Essentially, it puts us all on the same page. Sorely lacking in the assessment of threats to Greater Yellowstone has been a vision for pondering the future and the consequences of knee-jerk, short-term thinking.

Even if one doesn’t care about wildlife or something as precious as the ecological well-being of Yellowstone and the wild inheritance that Greater Yellowstone represents to this country, there are compelling reasons why it makes sense to pay attention to poorly-planned growth. Sprawl is the enemy to mom and pop farmers and ranchers, making it incredibly difficult to keep operating at scale. Rural communities have been an invaluable part of local identity. Rural sprawl also represents a financial liability to counties and should be of major concern to elected leaders who pride themselves on being fiscally responsible.

Cost-of-service studies show that many counties are struggling to meet the added need for expanded law enforcement, fire-fighting, emergency services, road maintenance, water and sewer services that new exurban denizens demand. This means that citizens who are already deeply concerned about how sprawl is already transforming the natural character of their community are given the added indignity of subsidizing the very kind of sprawl they don’t want.

Just as Americans are rightfully concerned about the lack of a coherent immigration policy on the U.S. southern border with Mexico, so, too, are longtime inhabitants of Greater Yellowstone worried about the downsides of inward migration to their region. A common lament is that rural valleys prized for their peaceful ambiance, unblighted views and presence of wildlife are being transformed into the kind of sprawl synonymous with the Front Range of the Rockies in Colorado or the west side of the Wasatch pressing north and south of Salt Lake City. There, the kind of wildlife values which still exist in Greater Yellowstone are long gone and no amount of expensive re-wilding can ever recover them.

Here, I wish to offer one last aside. Today, billions upon billions of public and private dollars are being spent trying to restore the ecological function of the Florida Everglades. Billions more are being spent to try to save imperiled wild salmon populations by retro-fitting or tearing down dams that have destroyed ancient spawning runs. In southern California, upwards of $100 million is being spent completing an unprecedented wildlife overpass, across 10 lanes of traffic, to accommodate a relative handful of mountain lions and other species that are barely able to persist in that highly fractured megalopolis. Prominent scientists say the least expensive way of maintaining wild nature is not to mess up what isn’t already broken and to prevent de-wilding rather than trying to address it in a reactionary way after the fact.

While NumbersUSA has produced several important analyses on the negative impacts of sprawl, this one, which you now hold in your hands or view on a screen, is arguably one of the most consequential. This study provides an opportunity for those in charge of charting Greater Yellowstone’s future to think differently and depart from following the script of growth that has brought the thoughtless ruination of wildlife ecosystems in other places.

Such an overview can be useful as a policy tool for two reasons: First, it helps identify areas of high value to wildlife that need to be protected. Secondly, it highlights places that can be sensibly developed and, in that way, brings predictability, order and better efficiency to elected officials and investors in the business community. Currently, this is not happening in Greater Yellowstone, and, in fact, most leaders will admit that the approach to dealing with growth to date has been haphazard, contentious, poorly articulated and not well understood by the public.

Remember this about Greater Yellowstone. Yellowstone National Park, its beating heart, is one of the most recognized place names on Earth. It ranks high on bucket lists of millions of people around the world as an essential destination to visit before they die. It is also a source of common national pride for Americans and an icon of intergenerational pilgrimage whose value has only grown over time and will continue to so long as we keep it healthy.

Before you digest the findings of this unprecedented analysis, let me leave you with a couple of lessons I’ve learned in writing about conservation on assignments that have taken me around the world. Land conservation typifies what it means to be conservative and it invites us to contemplate how we can do positive things that benefit others beyond the span of our own lives. In the history of the world, there are few examples where conservation has not, over time, demonstrated a profound accruing value in ways too manifold to mention. Finally, there is only one Yellowstone and one Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. If we can’t succeed in protecting this bioregion, then what hope, really, do we have for saving anyplace else?

TODD WILKINSON has been a professional journalist since 1985 and is recognized nationally for his reporting on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and other wildlands of the world. His work has appeared in dozens of national magazines and newspapers, including National Geographic, The Guardian, Christian Science Monitor and The Washington Post. He has won several awards and he has penned several acclaimed books on such topics as scientific whistleblowers, the journey of Ted Turner as an eco-capitalist/philanthropist/conservationist, the life of Jackson Hole Grizzly 399 and several books on art and business. His recent book, Ripple Effects: How to Save Yellowstone and America’s Most Iconic Wildlife Ecosystem, won three awards. He also is founder of a new conservation journalism site, Yellowstonian yellowstonian.org, devoted to exploring the importance of wildlife.