by Leon Kolankiewicz

I lived, went to grad school, and worked in the American West for 18 years. There I was a resident of British Columbia, Canada; Alaska; Washington state; Honduras, Central America; New Mexico, USA; and California.

During all those years, and a ton of adventure travel to great places – I made it to all 50 American states and all 10 Canadian provinces – I never once found my way to Yellowstone National Park, Grand Teton National Park just to its south, and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem writ large.

But I never forgot that these extraordinary open spaces and wild places were on my personal bucket list.

They had been for more than 50 years, when I first read Margaret and Olaus Murie’s 1966 book Wapiti Wilderness as a restless high school student growing up and daydreaming about wild nature in the less-than-wild suburbs of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania back when it was still “Steel City.” Wapiti Wilderness is a classic of the frontier Western and wildlife genres. (“Wapiti” is a Native American word for elk.)

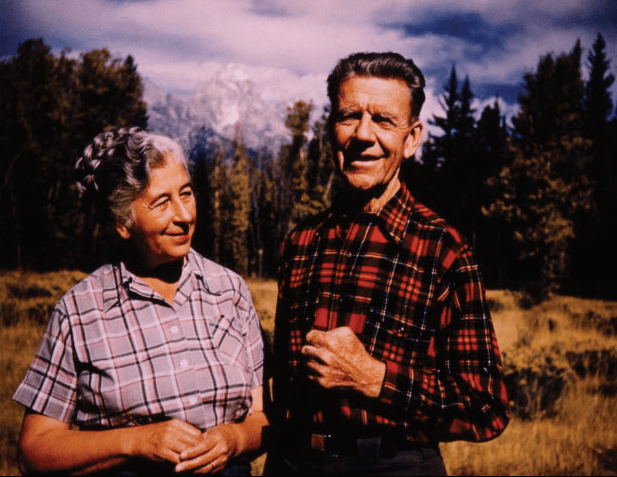

Margaret (Mardy) and wildlife biologist and native Minnesotan Olaus met in Fairbanks, Alaska, where he had gone to study caribou at the behest of my old employer, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS; back then it was called the U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey). Born in Seattle in 1902, Mardy and her family had moved to Fairbanks when she was nine.

Mardy Murie as an adventurous young woman in Alaska

In 1924, a century ago, Mardy became the first woman to ever graduate from the University of Alaska (then called the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines); that same year she and Olaus married at sunrise in the native Athabaskan village of Anvik in southwestern Alaska. They honeymooned on a 500-mile expedition by dogsled in the rugged and remote Brooks Range of northern Alaska, studying birds and conducting research on caribou. Mardy wrote evocatively about this quintessential wilderness experience in her book Two in the Far North.

They honeymooned on a 500-mile expedition by dogsled in the rugged and remote Brooks Range of northern Alaska, studying birds and conducting research on caribou. Mardy wrote evocatively about this quintessential wilderness experience in her book Two in the Far North.

In 1927 the Muries moved to the then frontier settlement of Jackson, Wyoming, on the edge of the majestic Grand Tetons. Here Olaus, still with USFWS, researched Rocky Mountain elk and ungulate ecology, with Mardy and their three children often at his side on field trips that could last for weeks. He later came to be called the “father of modern elk management.”

In 1945, the Muries, along with Olaus’ brother Adolph and sister-in-law Louise, purchased a former “dude ranch” in the area of Jackson Hole fittingly called Moose. (Adolph was also an eminent wildlife researcher and the author of a classic study of wolf packs, also set in Alaska, The Wolves of Mount McKinley.) Olaus and Mardy built a rustic but comfortable log home and other buildings (such as Olaus’ studio), which, to quote the National Park Service, “hosted pivotal conservation discussions that would lead to the protection of America’s wild places.”

During these busy years, Olaus served as president of The Wilderness Society and The Wildlife Society, among other professional and conservation roles. These efforts paid off with the passage of the landmark Wilderness Act of 1964, though Olaus did not live to see that legislative achievement, having died the year before. Mardy outlived him by four decades, continuing to reside in the home they had built and shared, ultimately reaching the ripe old age of 101.

Dubbed the “Grandmother of the Conservation Movement,” Mardy was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Clinton in 1998. Among her many admirers was celebrity musician John Denver, who dedicated a song to her and Olaus; one of Denver’s last concerts before he died in a tragic 1997 plane crash was at the Mardy Murie Film Benefit in Jackson.

Mardy and Olaus Murie and near their Moose home in the Grand Tetons of Wyoming, 1953

Murie residence in Moose, WY; May 2024

In recognition of the formative role it played in the history of the conservation and wilderness preservation movements, the Murie Residence in Moose, WY was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1990. The Murie Ranch Historic District was made a National Historic Landmark in 2006. Today, the Murie Ranch hosts a conservation organization named for Mardy and Olaus.

Last week, in a site visit as part of NumbersUSA’s forthcoming study on the threat posed by urban sprawl to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, I finally got to visit the fabled Murie ranch at last, after a wait of more than half a century.

It felt much like a pilgrimage to a shrine of sorts. The residence and historic district are located just half a mile from the Grand Teton National Park visitor center in Moose, and can be reached by walking along a lovely, level path through the sage meadows and evergreen forest, or by car on an unpaved road; I chose the former. Fittingly, I saw several elk, the animals to which Olaus dedicated much of his scientific career, feeding on the edge of the meadow.

As I gazed quietly on the Murie residence and Olaus’ studio 40 yards away, under the lengthening shadows of the tall timber, I reminisced back half a century (1974-1975) to my own two-year stint as a biological technician with the USFWS at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Laurel, Maryland. There, as a 19-year old, I was befriended and mentored by noted USFWS waterfowl and wetland biologist Francis Maury Uhler, with whom I formed a fast friendship, in spite of the 50-year gap in our ages. “Fran” was a native Minnesotan with Scandinavian roots like Olaus, and as I learned, a friend of the Muries; he even showed me a tiny figurine carved out of walrus tusk from Alaska that had been given to him by Olaus.

Just down from my supervisor’s office in the Merriam Lab at Patuxent was a herbarium, with stacks of drawers containing pressed plant specimens painstakingly collected from around North America by botanists and USFWS biologists generally. I would often linger here, perusing the collection; the oldest specimens dated back many decades, but they remained well-preserved. I marveled whenever I saw specimens collected by Olaus himself, because I already knew who he was from having read Wapiti Wilderness in high school.

Getting back to the present, I actually visited the Murie Ranch twice during my recent stay in Jackson Hole. I had the trail all to myself both times, and it was very gratifying that the same natural beauty and sense of solitude I savored for those precious moments had also been savored over the decades by Mardy and Olaus Murie all those years ago.

Path to the Murie Ranch from the Grand Teton National Park visitor center; May 2024