Unending Population Growth and Development Threaten the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

One thing we know: There is an almost universal recognition of the downsides and negative side-effects of sprawl on nature and humans, no matter who we are. Another thing we know is that sprawl is the result of not thoughtfully planning for the future. And in the case of what sprawl brings to landscapes the physical impacts are often permanent, costly to remedy and cumulative. Sprawl is an expression of how and where people live. The paradox of this report is that the most serious ecological impacts in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem are being exacted today by a rapid influx of what could be called “lifestyle migrants” with economic upward mobility but whose ecological footprint is disproportionately larger than that which, per capita, has historically existed in the region.

We understand there are some general concerns and preconceived opinions about efforts to reduce overall immigration to the United States, especially when it comes to enforcing laws against illegal immigration. It is our desire to address these concerns and opinions up front and in good faith with a sincere hope that our unprecedented analysis on how sprawl is transforming the ecological function of Greater Yellowstone will be reviewed and digested by readers from all backgrounds and political dispositions with an open mind and an open heart.

Just as investigative journalist Todd Wilkinson writes in his inspiring Foreword to this study, let’s be clear: Unless things change, unbridled growth is going to ruin many of the things that still set Greater Yellowstone apart as a national natural treasure. One of the things Todd says that is often missing from the conservation equation is empathy and compassion for wildlife being impacted by sprawl and our inability or lack of awareness in seeing the impact of human development through the eyes of those non-humans whose habitats (living spaces) are being permanently erased – this in a country and world where already much has been lost.

The fate of Greater Yellowstone is in our collective hands, so what will we do with the opportunity and responsibility to act?

Many people ask: why advocate for less immigration to America? NumbersUSA was founded in 1996 to promote the recommendations of two federal commissions from the Clinton administration – the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform and the President’s Council on Sustainable Development. Both commissions called for a lower annual immigration admission level for economic and environmental reasons. We encourage you, the reader, to familiarize yourself with the history, the intentions, and the specific recommendations of these two federal commissions. Context is important.

We, the authors at NumbersUSA, have been especially influenced and inspired by the late, great landscape-scale conservationist Dave Foreman. Foreman called himself a Barry Goldwater Republican in his youth but he evolved into what he self-described as “a citizen with a social and ecological conscience.” He often emphasized at public events that healthy landscapes benefit everyone and the best kind are those that inspire and are paid forward into the future. Landscapes that hold their biological diversity serve as a gauge for measuring ecological health and sound ecological health is the foundation for healthier human living. Such places are not only the wellspring for flora and fauna but clean air and water, counterpoints to the crowded blight of megacities, and safeguarding nature is a shrewd investment in the hope of having a more livable world. Of immigration and intra-migration, Foreman wrote:

“We need to speak more from the question of how many not who. To get out of the thicket, we need to help people understand that cutting immigration is not anti-immigrant and not tied to nativism or racism, but tied directly to our ecological future.”

That is a powerful statement! Its power rests in its truth and it gets at the vexing question of humans loving wild fragile places to death and the more recent trend of building upon them, sealing them forever in tombs of asphalt, concrete, steel and fragmentation that disconnects us from the healthy, health-nurturing biota. There is a parallel between unplanned immigration that occurs across national borders and “intra-migration” that occurs inside countries.

By now it shouldn’t be a secret that America’s immigration policy (including legal and illegal admissions) is the primary driver of population growth nationally. Growth in our numbers has long been linked to environmental degradation and a deteriorating quality of life for humans and non-humans alike. One compelling example of this is sprawl, which Todd Wilkinson rightly asserts has an established record of being a thoughtless destroyer of wild ecosystems. Sprawl is not only a serious ecological concern and an economic, social and cultural one, but it represents the greatest ongoing threat to the integrity of public lands and public wildlife of which all of us are stakeholders. This is empowering, not disempowering. A rare wonder like Greater Yellowstone is something that we, together, can choose to bequeath intact to future generations. Fifty years from today, people can look back and say we protected habitat for grizzlies and wolves, bison, game species, open space and terrain vital to working ranchers and farmers and be grateful. Or, we can ignore the trendlines visible on the ground. It’s our choice.

This is why NumbersUSA has produced the report you have in front of you. We hope it helps serve as a tool for thinking about a special ecosystem. We welcome your open-minded consideration and your critical review of this analysis. Our goal is your goal: to preserve a wild and thriving Greater Yellowstone and prevent the loss of this uniquely beloved national natural treasure. We have one chance to get this right. Together, let’s have a meaningful discussion. Let’s succeed together.

In his Foreword to this study, veteran Greater Yellowstone investigative journalist and author Todd Wilkinson writes that:

Greater Yellowstone, if you’re unfamiliar with it, has Yellowstone, the first national park in the world, at its geographic heart. The ecosystem that encompasses the park is today considered the most iconic wildlife-rich bioregion in the Lower 48 states, renowned especially for its concentration and diversity of large free-ranging native mammal species rescued from near-annihilation at the end of the 19th century.

Figure ES-1. Bison overlooking the rapidly growing Gallatin Valley of Montana, in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem north of Yellowstone National Park

Unless otherwise noted, photos in the Executive Summary are by wildlife photographer Holly Pippel

Wilkinson goes on to compare the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) with the world-renowned Serengeti Plain in East Africa, a comparison also invoked in our study’s first chapter: “Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: America’s Besieged Serengeti.” A visitor to Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks at the core of the GYE will soon notice their international reputation. This is borne out by the sight of many foreign visitors paying homage to the majestic mammals of America’s own Serengeti and the sound of the many languages in which they extol the parks’ scenic and geological extravaganzas.

The GYE is the only substantial ecosystem remaining in the Lower 48 states (i.e., excluding Alaska and Hawaii) which still boasts the entire array of species here in 1491, the year before Europeans “discovered” the Western Hemisphere. Among the charismatic megafauna found then and now are grizzly and black bears, timber wolves, coyotes, mountain lions, wolverines, moose, elk, mule deer, bison, pronghorn, and mountain sheep.

Figure ES-2. Grizzly bear in the GYE

Yet a century ago, three of these species – the grizzly bear, wolf, and bison – had already been virtually eliminated from Greater Yellowstone and much of the American West – or were well on the way to being so. The relative recoveries of their GYE populations to stable or increasing numbers are in fact great success stories in wildlife conservation, and the science, management, and crucial popular support that undergird that.

Of the GYE’s 23 million acres, about three-quarters are public lands and the remaining one-quarter privately-owned, mostly working farms and ranches, although that is changing as the region’s human population burgeons and more and more areas are paved over or built upon. Such development accommodates the needs and demands of the newcomers for developed or urbanized land, not just their homes, driveways, and patios, but related commercial areas, utility infrastructure, streets and roads, schools, office parks and other job sites, recreation areas (e.g., soccer fields, tennis courts, golf courses), and so forth. In aggregate, the average resident uses or “consumes” more than half an acre of developed or urbanized land.

As Wilkinson notes, four factors once helped safeguard the GYE’s wild character: geographic remoteness, the sheer extent of public lands, low human population, and the fact that most private lands were either agricultural (farmland/ranchland) or undeveloped open space. Nowadays however, three of these four factors – remoteness or geographic isolation, low human population, and development confined to urban areas – no longer prevail.

The GYE’s private lands are situated mostly in river valleys and lower-elevation settings. Because of this they play a pivotal ecological role out of proportion to their relatively small area. As Wilkinson says, they “are like vital connective tissue holding together the superstructure of public lands.” Larger mammalian species in particular depend on habitats on these private lands, especially in the punishing Northern Rockies winters.

A short hike from the visitor center at Grand Teton National Park sits the Murie Ranch, dubbed the “heart of American wilderness” by the National Park Service. Here for much of the 20th century lived various members of the Murie family: Wilderness Society director and wildlife biologist Olaus Murie, his conservationist wife and author Margaret (Mardy), his brother and fellow wildlife biologist Adolf (author of the classic study The Wolves of Mount McKinley), and an evolving assortment of family members, friends, colleagues, and wilderness enthusiasts and advocates.

Figure ES-3. Working farms and ranches are an important land use on lower elevations in the GYE

Greater Yellowstone is a crucible of the American wilderness preservation movement nearly as much as it is for conservation biology. As writer, filmmaker, and conservationist Lois Crisler famously observed in her 1956 classic Arctic Wild: “Wilderness without wildlife is just scenery.” Human overpopulation is incompatible with both authentic wilderness and the wildlife denizens of wilderness. This was recognized clearly and forcefully by the late U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson, the “father” of Earth Day, and in the final stages of his illustrious career, a counselor to the Wilderness Society. At a March 2000 speech in Madison, Wisconsin, Nelson asked the audience: “With twice the population, will there be any wilderness left? Any quiet place? Any habitat for songbirds? Waterfalls? Other wild creatures? Not much.”

A searing expression of this fundamental incompatibility reached us as we were drafting this executive summary. According to an October 23, 2024 press release of the National Park Service:

On the evening of Tuesday, October 22, 2024, grizzly bear 399 was fatally struck by a vehicle on Highway 26/89 in Snake River Canyon, south of Jackson, WY outside of Grand Teton National Park. The bear’s identity was confirmed through ear tags and a microchip.

Figure ES-4. Grizzly bear 399 with one of her 18 cubs

National Park Service photo by C.J. Adams

Figure ES-5. It’s not just grizzly bears; elk startled by oncoming vehicle

Grizzly bear 399, known as “the Queen of the Tetons,” was a 28-year-old female believed to have been born in 1996; she was documented to have birthed 18 cubs, raising eight of them to maturity. She was the most beloved bear in America and perhaps the world. 399 was even the subject of an adoring PBS Nature documentary earlier this year. But in the wake of the news of the all-too-predictable manner of her demise, one heartbroken conservationist wrote: “Such a dishonorable end to her majestic life and contribution to the GYE.”

399’s tragic death sadly symbolizes the implacable, unrelenting reality faced by Greater Yellowstone’s large mammals as the human population, visitation, development/sprawl, and vehicular traffic all increase without apparent limit in this beleaguered wildlife paradise. This is what our Greater Yellowstone sprawl study is about.

Greater Yellowstone’s iconic wildlife populations – while in many respects better off today than they were half a century ago or a century ago due to scientific, modern wildlife management and broad public support – nonetheless face a number of pernicious, stubborn, and growing threats, among them novel diseases, invasive species, jurisdictional squabbles, and climate change. Arguably the most significant threat of all though is habitat loss, fragmentation, and blockage of ancient ungulate migration corridors because of widespread, rampant development.

In recent decades, population growth, development, and sprawl on private lands within the 20 counties that comprise the GYE have permanently converted hundreds of square miles of open space – all of it agricultural land, wildlife habitat, or both – into developed or urbanized land. Resulting habitat loss and obstruction of traditional wildlife migration corridors have adversely impacted the ecological integrity of the GYE and its extant populations of large ungulates and carnivores. Worldwide, habitat loss and fragmentation are widely acknowledged as the single greatest threat to biodiversity and viable wildlife populations.

Figure ES-6. Squeezed out: Wintering elk in the GYE’s Gallatin Valley are crowded into fragmented patches of habitat as they lose ground to sprawling residential development

The GYE supports long migration corridors for elk, pronghorn, and mule deer that extend well beyond national park and forest boundaries into and across private lands vulnerable to development. Over the coming decades, current and projected rates and patterns of development in much of the GYE would severely constrict or wipe out key wildlife migration corridors.

This study quantifies the respective roles of two fundamental factors that drive increasing development on non-federal (mostly private) lands in the 20 counties that comprise the GYE: 1) population growth, and 2) increasing per capita land consumption (i.e., declining population density).

Our team uses a mathematical formula originally developed to assess the relative weights of increasing population size and per capita energy use in determining the nation’s aggregate energy consumption. This “apportioning” approach can be applied to any natural resource whose aggregate consumption is increasing over time, due to a changing number of resource consumers, changing per capita resource consumption, or both. In this study, rural, undeveloped land – that is, farmland/ranchland and wildlife habitat – is the natural resource in question.

We use “longitudinal” data (which track changes over time in something we are measuring) from two federal agencies: the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS, formerly the Soil Conservation Service or SCS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Census Bureau (USCB). NRCS National Resources Inventories (NRIs) have estimated land use and cover on America’s non-federal lands county-by-county every five years since 1982.

One of the NRI’s land use categories is “developed land,” which documents changes in 5-year intervals in the estimated area of developed or built-up/paved lands in any given county, such as the 20 counties of the GYE. USCB estimates county populations annually. With both datasets available from 1982 to 2017 (35 years), we derived estimates of the percentage of sprawl (defined as conversion of rural to developed land) in the GYE related to population growth and to increasing per capita developed land consumption.

“Per capita developed land consumption” refers to how much developed or urbanized land is associated with any given resident of a county on average, and it is simply the area of developed land in a county (according to the NRI) divided by the county’s population (according to the USCB).

Figure ES-7. Example in the GYE of what would count as “Developed Land” in the NRI

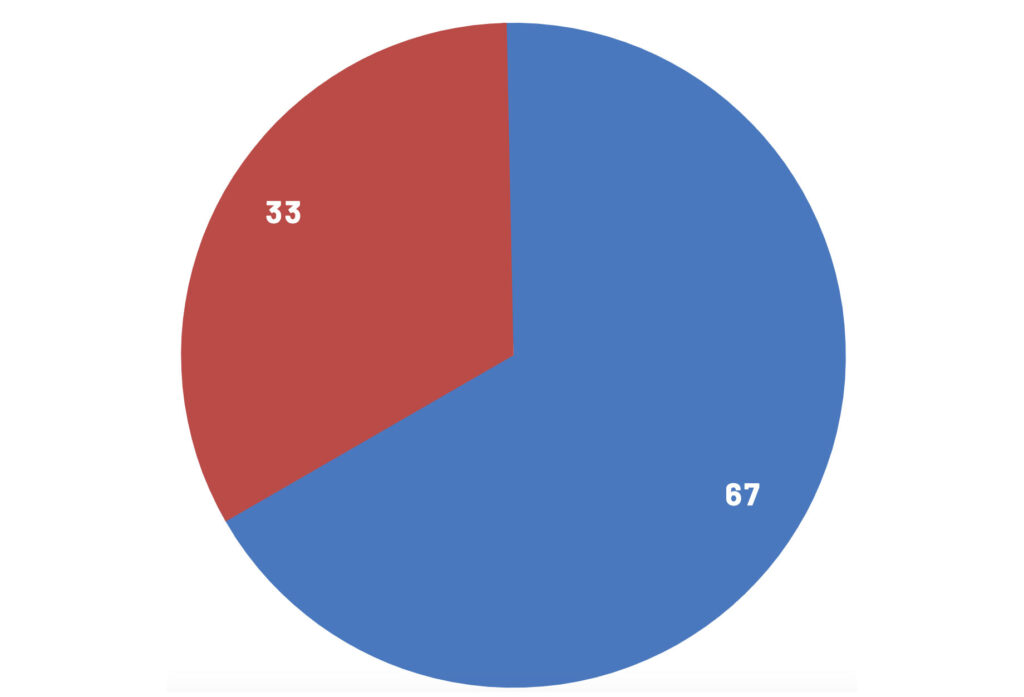

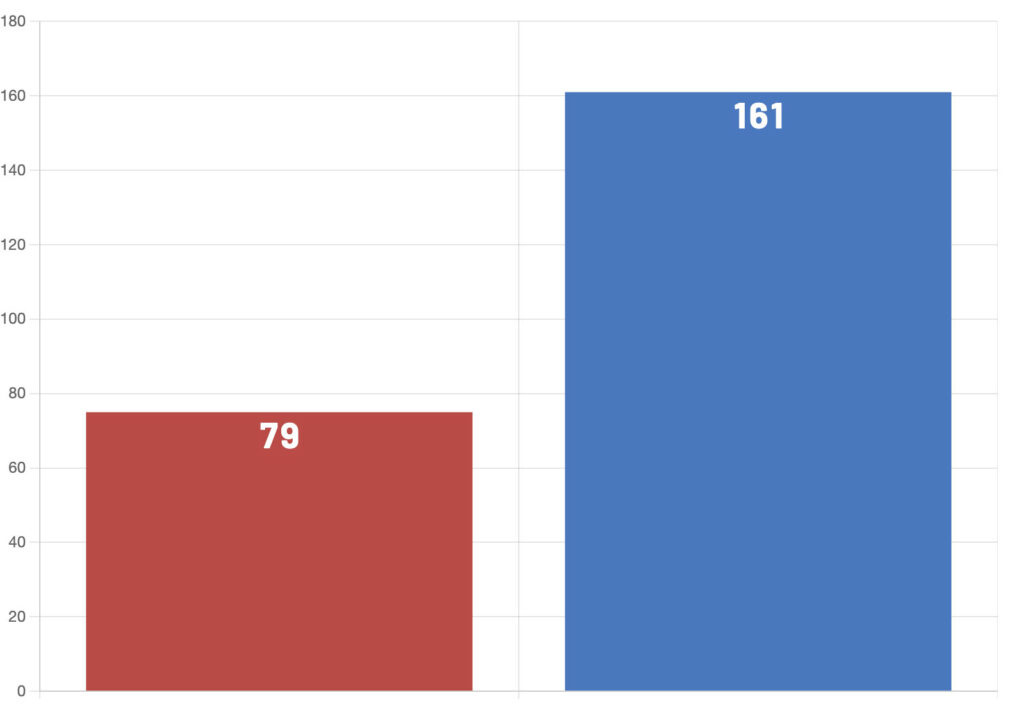

The area of developed non-federal land in the 20 GYE counties grew from 345,300 acres (539.5 square miles) in 1982 to 497,400 acres (777.2 square miles) in 2017, an increase of 44% or 152,100 acres (237.7 square miles). Approximately 67% (161 square miles) of this increase was related to population growth and 33% (79 square miles) to increasing per capita developed land consumption (Figures ES-8 and ES-9).

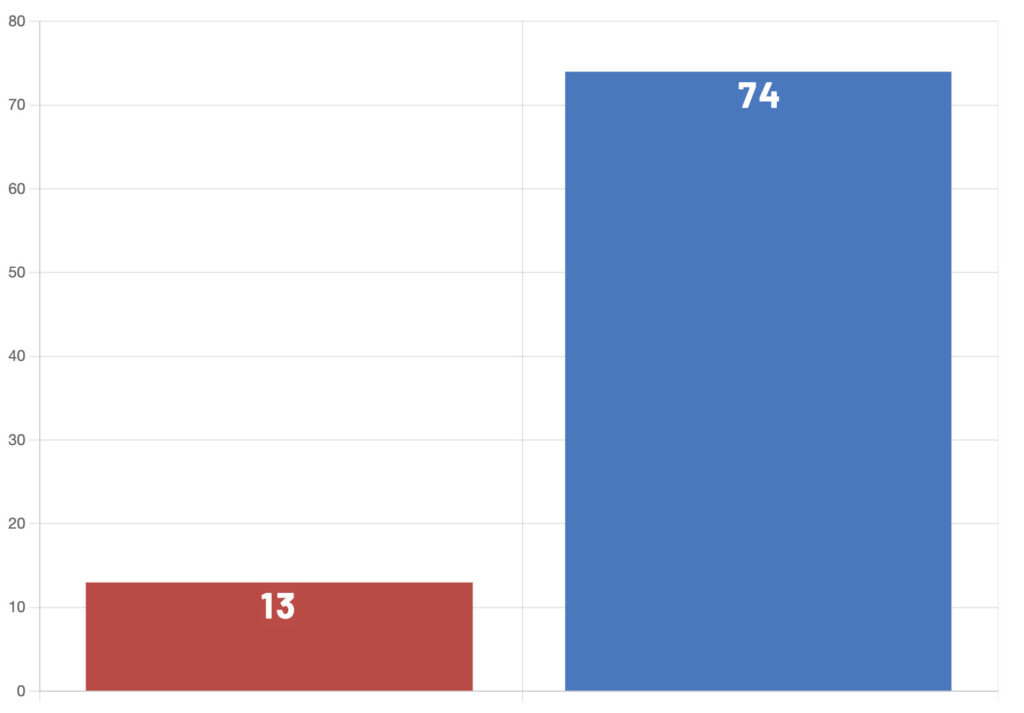

Percent of GYE’s 1982-2017 sprawl (conversion of rural to developed land) related to increasing per capita land consumption

Percent of GYE’s 1982-2017 sprawl (conversion of rural to developed land) related to population growth

Figure ES-8. Sprawl Factors (Increasing Population and Increasing Per Capita Land Consumption) in GYE Counties, 1982-2017

Square miles of sprawl related to increasing per capita developed land consumption

Square miles of sprawl related to increasing population

Figure ES-9. Rural Land Lost to Population Growth vs. Per Capita Sprawl in the 20 Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem Counties, 1982-2017

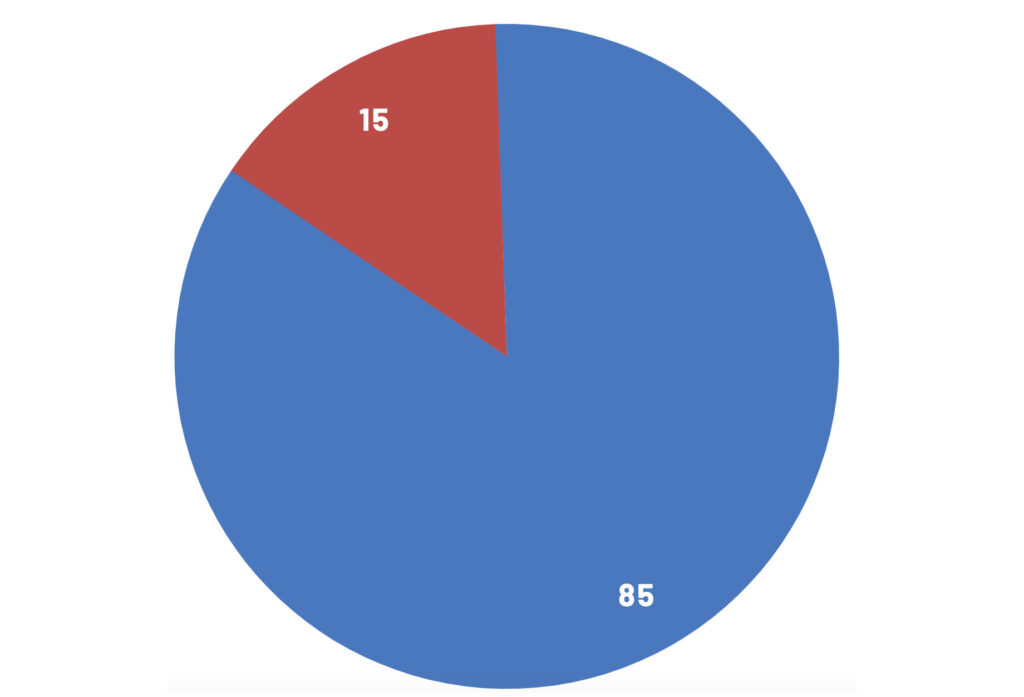

In the most recent 2002-2017 subset, an even higher portion of the sprawl, 85%, and rural land lost to development were related to population growth (Figures ES-10 and ES-11). These results may underestimate the adverse effects of low-density exurban sprawl on habitat fragmentation and large mammal migration. This driver has grown especially pronounced since the Covid-19 pandemic, as wealthy out-of-staters have moved into the GYE from places like California, building large homes and ranchettes on often fenced large lots, which themselves can pose barriers to large mammal movement (Figure ES-12); this trend shows no sign of letting up.

Percent of GYE’s 1982-2017 sprawl (conversion of rural to developed land) related to increasing per capita land consumption

Percent of GYE’s 1982-2017 sprawl (conversion of rural to developed land) related to population growth

Figure ES-10. Recent Sprawl Factors (Increasing Population and Increasing Per Capita Land Consumption) in GYE Counties, 2002-2017

Square miles of sprawl related to increasing per capita developed land consumption

Square miles of sprawl related to increasing population

Figure ES-11. Recent Rural Land Lost to Population Growth vs. Per Capita Sprawl in the 20 Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem Counties, 2002-2017

Figure ES-12. Leaping over a property fence; not all wildlife can or do make it across such proliferating barriers

Under current demographic trends in the region, by 2060, the aggregate population of the GYE counties is projected to grow to 763,471, from 538,702 in 2022, an increase of 224,769 or 42%.

If average population density were to remain constant, this growth would lead to the conversion of approximately another 231,500 acres (362 square miles) of non-federal rural land (e.g., natural habitat, ranchland) to developed properties. These newly developed areas would be unevenly distributed at varying densities throughout the GYE. In sum, their aggregate area and configuration – and the concomitant habitat loss and fragmentation – would entail potentially significant adverse, long-term direct, indirect, and cumulative effects on wildlife, especially large mammals with large home ranges and/or long seasonal migration routes.

Avoiding this unacceptable, unthinkable outcome will require a combination of: 1) effective local, regional, and statewide planning measures and 2) commitment to national population stabilization. Each is necessary, neither is sufficient in itself, to preserve the unique character and iconic wildlife of the world-class GYE.

With regard to #1, examples of such measures include:

These measures and others have all been implemented with varying degrees of success in communities throughout the country. They would have the net effect of accommodating – not stopping – new population growth by increasing population density on new and already developed areas. In the GYE, these planning measures would require local political support and cooperation within and across three states and multiple jurisdictions.

A public opinion survey conducted of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming likely voters by Rasmussen Reports in conjunction with our study indicates that nearly two-thirds do favor using such planning tools as a means of limiting sprawl.

It should be noted that these measures, even if effective at reducing the rate of habitat loss and fragmentation, would do little to slow the growth of vehicular traffic on regional highways that in and of itself will increase wildlife mortality from more collisions.

With regard to #2 above – commitment to national population stabilization – this is also crucial because demographic pressures to migrate to “last, best places” like Greater Yellowstone will only intensify in coming decades if overpopulated states such as California and Texas continue to fill up and see their quality of life eroded.

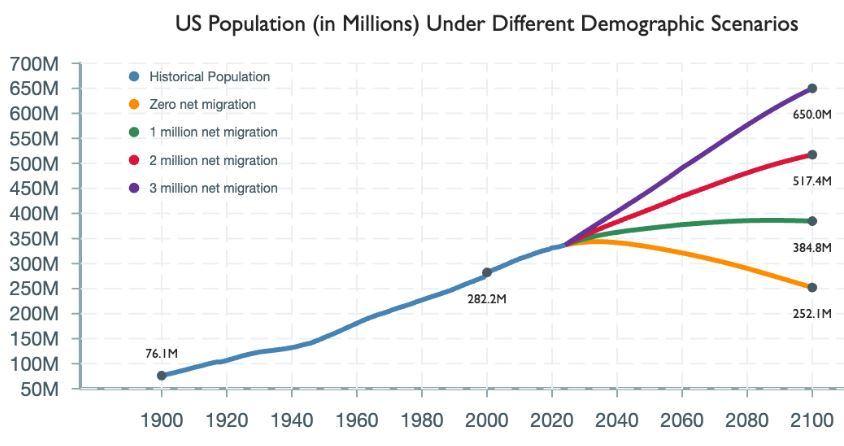

Figure ES-13 depicts four population projections to the year 2100 for the United States based on Census Bureau methodology; these scenarios differ by assumed levels of net immigration into the country. With U.S. fertility predicted to remain well below replacement level (where it has been for the past half century), immigration is expected to drive almost all future U.S. population growth. Net migration of 3 million in the highest projection in ES-13 would lead to a U.S population of 650 million by 2100, a near-doubling of our present numbers.

It is worth noting that in 2023, under the Biden administration’s policies, America experienced net migration of approximately 3 million, thus these numbers, while unprecedented and unsustainable, are not far-fetched.

Figure ES-13. U.S. Population Projections to 2100 under Various Immigration Scenarios

Americans in general and residents of the three GYE states in particular are concerned about population growth and support stronger measures to slow it down, at both the national and regional levels. In the July 2024 Rasmussen Reports survey of 839 likely voters in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming that accompanied our study:

To reiterate, both local and national efforts are essential to ensuring the future of wildlife in Greater Yellowstone.

Earlier we mentioned the sad symbolism of the tragic death of grizzly bear 399 in late October 2024, fatally struck at night by a moving vehicle on a highway in the Snake River Canyon near Jackson. She was the single most beloved bear in America and likely the world.

Our colleague and Greater Yellowstone’s most eloquent defender Todd Wilkinson wrote a moving essay for National Geographic on why 399 mattered to Americans and the world. He shared some additional thoughts with us via text message:

…399 was struck and killed on a highway, one of many in Greater Yellowstone being busier due to growth-related issues and those traffic lanes are fragmenting habitat.

The solution is not merely to build more expensive wildlife bridges but better plan to protect habitat on both sides of the highway, as sprawl is rapidly shrinking options for the region’s world-class wildlife to navigate…

399’s tragic death should be part of a wake-up call and the best way people can honor her legacy is by engaging in serious ecological thinking that ensures grizzlies following in her wake have the secure habitat they need to sustain a healthy population of bears. What’s good for bears is also good for hundreds of other species, large and small.

Figure ES-14. This should be the future of the GYE…

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is a national treasure, without a doubt, but even this “pristine” area is under threat by growth and development. The allure of “wild, wide open” spaces is why so many people wish to visit, and why an increasing number of people are choosing to live there permanently. This is the conundrum we have created for ourselves. We are inherently drawn to the beauty of undeveloped land, and in order to be nearer to “nature,” we develop those lands, destroying their wild character forever.

As environmental activist Jordan Perry so succinctly put it, “The nature of consumption is the consumption of nature.” There is no way around it, humans must consume in order to survive and propagate. But at no time before us has so much been consumed by so many. There is more to life than maintaining three percent annual GDP growth, but you wouldn’t know it by listening to experts, elected leaders, and even many of the louder voices within the environmental movement, who mostly support perpetual growth as long as it’s “smart” or powered by supposedly “green, renewable” energy sources.

Most Americans have been conditioned to think of “the environment” in abstract terms, not as the place where we all live, wherever we live. We need to change that way of thinking. Every action an individual takes has an effect on our environment, and the preservation of “wild, wide open” spaces is essential to human flourishing. Collectively we must come to terms with that reality while committing ourselves to minimizing irreversible damage to ecosystems. When it comes to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, that means realizing that there are limits to growth and acting accordingly; or admitting that we are committed to the proposition, as ludicrous as it is, that we can grow forever while still managing somehow to live sustainably.

Figure ES-15. …not this